Tom Metzger, American Radical

(April 9, 1938-November 4, 2020)

Posted By Jim Goad On November 12, 2020 @ 3:45 am In North American New Right

Terrible Tommy Metzger died the day after the election.

One night in the fall of 1989 I was a snot-nosed and cocksure wigger journalist who’d tooled the hundred miles or so south from my ratty apartment a half-block from Frederick’s of Hollywood to interview Metzger at his home in Fallbrook, CA.

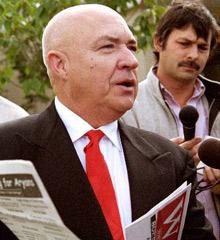

At the time, Metzger, who made a living as a TV repairman, was the highest-profile face of white supremacy. . . or white nationalism. . . or white separatism. . . or at least unapologetic whiteness. . . in the country, soon to be eclipsed by David Duke, under whom Metzger had formerly served in the KKK. Duke didn’t start to snag national headlines on a large scale until his 1990 run for the US Senate in Louisiana.

It was also in 1990 that Morris Dees and his SPLC won a successful $12.5-million civil suit against Metzger, his son John, and Metzger’s organization White Aryan Resistance (WAR), blaming them for the beating death of an Ethiopian man named Mulugeta Seraw on the Portland streets by white-power skinheads in an incident that Metzger, to his death, insisted was a mere street fight gone bad rather than a deliberate racial attack on a colored fella who’d innocently been minding his own business walking around late at night as innocent colored fellas are wont to do.

The fact that Metzger did not know any of the killers did not impress the jury. Nor did the fact that he’d never told anyone to kill anyone. Nor was the fact that John and Tom Metzger were over 1,000 miles away from the incident when it happened. The sole piece of “evidence” that the SPLC used to bankrupt his organization was some vague message Metzger had left on his voicemail line about how he’d heard Portland skinheads were raising some hell up there and that he didn’t quite disapprove. Otherwise, there was absolutely no connection, direct or remote, between WAR and Seraw’s death.

That was 1990, and even back then the mere insinuation that someone was a violent racist Nazi was enough to prejudice a jury beyond all reason. Just like Vincent Bugliosi had convinced jurors in Charles Manson’s murder trial that Manson was guilty of murder simply because he had scary ideas, Mo Dees persuaded a group of sheltered Portlanders that Tom Metzger was responsible for murder even though he never even told anyone to kill anyone.

Although they never broke his spirit, Tom Metzger was one of the first to be targeted and bankrupted by the SPLC, which is why I see it as a minor tragedy that he was so forgotten and abandoned by so many of his ideological heirs, especially those who seek to aggressively distance themselves from whatever it was that they thought he did wrong and that they arrogantly assume they’re doing right these days.

Born in Indiana, which constantly vies with Nebraska as America’s bleakest state, Tom Metzger served in the US Army in the 1950s. He drifted toward anti-communism but by his own account felt alienated by the John Birch Society because they forbade the mere hint of Jew-naming. He achieved the rank of California’s Grand Dragon of the KKK until pivoting toward irreligious Third Positionism with a focus on reclaiming the streets that gradually earned him the unofficial role as paterfamilias of the American white-power skinhead movement.

In 1980, Metzger gained media prominence first by launching a successful campaign for the Democratic nomination for Congress in a district of Southern California despite being a proud former Klansman, a political coup that raised the ire of a young Maxine Waters [2].

The next time someone tries to tell you that we live in a “white supremacist” country, tell them that Tom Metzger languished in poverty and obscurity for the last 30 years of his life, while Maxine Waters lives in a million-dollar mansion and is still in Congress.

But even back in the early 1980s, Tom Metzger was desperately trying to spread the message that Republicans and Democrats were merely two arms on the same monster — and the message STILL hasn’t gotten across.

The Metzgers’ most famous moment in the spotlight was in 1988, a year before I interviewed Tom, on Geraldo when a group of skinheads cleared the stage [3] with an explosion of violence the moment black activist Roy Innis tried choking Tom’s son John. Geraldo wound up with a broken nose.

Good optics or bad optics, those were certainly some powerful optics. I can’t recall any time since where a group of white people defended a white person against violence with such a breathtaking display of retaliatory violence. Instead, I’ve heard “Dissident Rightists” squabble among one another for 30 years about how people such as Metzger fucked up “the movement,” because under the new guidance, America is, um, in much better shape than it was in the 1980s, even though many of the prophesies Metzger made back then that seemed dystopian and schizophrenic have been fulfilled.

But despite his organizational skills and the fact that he seemed to have a thousand eager wolves on a leash at a moment’s notice, Metzger’s chief talent was as an unapologetic spokesman who could disarm people with a mien as gentle as a kitten’s. He was the absolute first guest on a short-lived late-night Whoopi Goldberg talk show [4] in 1992, and look at how he has her eating out of his hand by the end of the show.

JDL thug Irv Rubin, incensed that Goldberg had given Metzger a platform, demanded equal time, which she granted him. This was shortly after 1992’s LA riots, and whereas Metzger had utterly charmed her, Whoopi was shooting daggers at the graceless and charmless Rubin after he spat out things such as “Jews don’t riot. What are we going to loot — libraries?”

After my interview with Metzger appeared in the Los Angeles Reader in late 1989 with the title “He Always Does the White Thing,” Rubin called me at the Reader demanding equal time. Unlike Whoopi, I was not so accommodating.

At one point during the interview I asked to use the Metzgers’ bathroom, and I remember being startled to see a copy of People magazine sitting there near the commode. A child of relentless media brainwashing just like any other American child, it didn’t occur to me that “Nazis” did anything but lynch blacks and throw darts at pictures of Jews. It seemed so disconcerting that one or more members of Tom’s family might want to read about the latest Kevin Costner movie or how the various members of Bon Jovi were handling rehab.

Like it or not, seeing People magazine there forced me to concede that, yes, the Metzger family was comprised of actual human beings who laughed, cried, and probably liked ice cream.

This is why they don’t allow you near people like the Metzgers anymore.

But it was Metzger’s response to a pointed question which I had considered a real “gotcha” that entirely flipped my egali-tarded worldview on its head. It was both the content of his response and the unconcerned manner in which he delivered it that changed the whole way I looked at the world. This was 31 years ago — more than half my life ago — and it was the last major ideological shift I’ve had; the first two involved tossing the script on Santa Claus and Jesus.

“You’re not big on equality, are you?” I arrogantly asked Metzger as if I’d cornered a rat.

“No,” he shrugged, “and neither is anyone in power. So when they say, ‘All men are created equal,’ I laugh, because no one in power believes that.”

I don’t think I uttered a response. Instead, I likely uttered a soft internal “Oh” and realized that he was right. No one in power feels equal to us — they obviously feel superior.

Metzger’s comment was not the only thing that shifted my perspective. I had started to gradually become disenchanted with Leftism because I am saddled with this unfortunate ability to notice patterns [5]. Innate inequality has a way of inconveniently poking out its head no matter how violently they try to suppress it.

So do the egregious double standards. It was around this time, while flipping through the WAR newspaper, that I noticed Metzger was peddling VHS tapes of British white-power punk band Skrewdriver. This was back when I happened to realize that while major music corporations were pushing violent black racial radicalism in the form of bands such as Public Enemy, there was nothing remotely equivalent for white kids. NWA would start selling millions — mostly to disaffected white suburban teens — while Skrewdriver wallowed in complete obscurity. The powers that be were propping up entities such as Maxine Waters and Niggas Wit’ Attitudez while they squashed Skrewdriver and Tom Metzger like so many White Aryan cockroaches.

With rare relish, Tom Metzger played the role of the evil grinning white-power gnome throughout the 1980s. The powers that be stepped in and destroyed him in the early 1990s while allowing the relatively inarticulate shitheads from NWA to become near-billionaires [6]. It’s clear who the true American radical was back then. Hint: It wasn’t Dr. Dre or Ice Cube.

One needn’t become a violent skinhead to see the truth in some of what Metzger was saying. With an impenitent smirk, he said many things [7] that are simply common sense once you extricate them from the theatrics and how outrageous they seem in the broader cultural context — things such as “Fifty-five million people died in World War II, and all people wanna do is cry about the Jews; what about all the rest of the people that died in World War II?”

Tom Metzger was one of the few to realize how fruitless it is to worry about optics when the world is burning around you. He also had the rare ability to demolish entire worldviews with a simple shrug and a short, perfectly sensible answer to an emotionally loaded question.

It’s clear why they had to silence him.

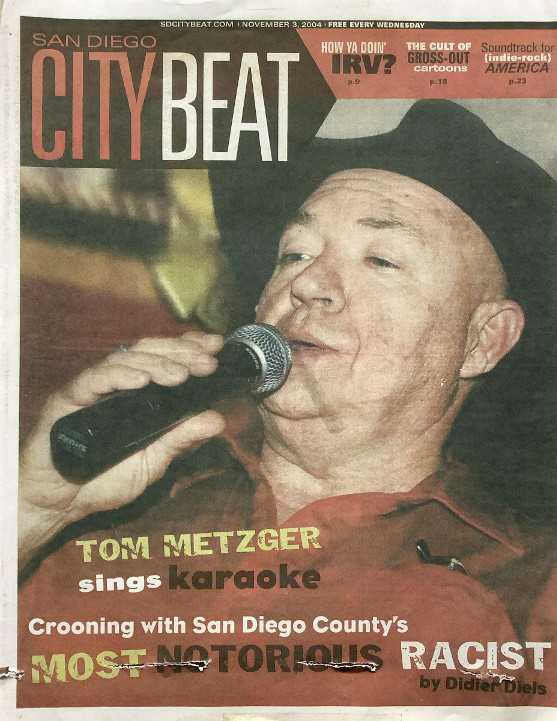

TOM METZGER SINGS KARAOKE

November 3, 2004

Crooning with San Diego County’s most notorious racist

by Didier Diels

photos by Derek Plank

Above the Village Barbershop, where he used to have his hair cut, when he had hair, and his toupees trimmed, when he still received them in the mail from his mother, Tom “Terrible Tommy” Metzger sits behind the bar at Ron’s Red Eye Saloon. Now 66, Metzger shaves his head, and the clean scalp, combined with diet and exercise, makes his face look lean, the skin, even with thick cheeks, pulled taut around his bright blue eyes.

For the last half-hour, he has talked above the saloon’s blaring pop-rock anthems about his mother and stepfather in Warsaw, Ind., an Army tour of Germany post WWII and leaving the family farm in an Austin Healy convertible bound for Santa Monica in the dead of winter. Metzger, the once dreaded Klansman and founder of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR), has fended off the advances of a pretty blonde half his age who has wandered by twice to say hello, wrap her arms over his broad shoulders and peck him lightly on the cheek. Underneath a black cowboy hat, he sips on a vodka and soda and scans the room. He is getting anxious.

The target of two assassination attempts, Metzger is not worried about security. Though an icon to white supremacists, he has no appointment to speak at a rally or charge up a group of skinheads for a night of lawless abandon. Not on Tuesdays.

“It’s almost 8,” he says, glancing at his watch like a nervous commuter. “I need to get in line to sing.”

Tom Metzger didn’t always sing karaoke. He picked up the habit in 1992, the year Kathleen, his wife of 28 years and mother to his six children, died of lung cancer, and the year a civil trial for conspiring to commit murder bankrupted him. Alone after the imprisonment of his son on criminal charges stemming from the same murder, and the departure of his five adult daughters, Metzger went on welfare and took up karaoke.

“I started singing to keep me occupied,” he says, pursing his lips with sudden sadness. “Otherwise, I’d be an alcoholic.”

In 1980, Metzger had no problem keeping occupied. He had just risen to Red Dragon (state director) of the Ku Klux Klan’s California chapter, moved his family to Fallbrook, a conservative town in rural north San Diego County, and decided to run for U.S. Congress.

With no budget and Metzger running his own campaign, he relied on media attention as a political sideshow—there was plenty—to compete in the Democratic primary. Newspapers and opponents laughed him off, and he took a beating in early polling along the coast, but as the vote moved east into the more conservative countryside, Metzger staged a comeback. By final tally the next morning, Metzger, the declared Klansman, had actually won.

“People were surprised,” said Lynn Orcutt, who cuts hair at the Village Barbershop. “I guess in the privacy of the voting booth, a lot of people actually agreed with him.”

Democratic Party leaders would steer clear of the race, rather than endorse Metzger, who claims he was barred at gunpoint from entering the nominating convention—but he would run for political office again in 1982, this time for U.S. Senate. Having abandoned the Klan—“They were too liberal,” he says, laughing warmly—Metzger somehow managed the necessary 75,000 signatures to get on the ballot as an independent, solely through his own supporters. In the general election, he lost badly, but as the white power movement swelled its ranks, so did the reach of Metzger’s infamy.

Through the 1980s and ’90s, magazines and sensationalist television reporters profiled hate groups with regularity. Fringe white militias—“those idiots running around the woods with rifles,” as Metzger describes them—inspired mainstream fear by running around the woods with rifles. A racist revolutionary, Tom Metzger was also a household name, arguably the most famous white supremacist in the world, right there with his friend David Duke, the former KKK Grand Wizard and eventual 1992 presidential candidate.

White fringe groups had also caught the government’s eye. No longer content to leave extremists be, federal agents launched bloody attacks, first at the farm of anti-tax activist Randy Weaver in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and later at the Branch Davidian compound of David Koresh in Waco, Texas. The anti-government, often racist, strain of white radicalism peaked on April 19, 1995, when Timothy McVeigh detonated a Ryder truck full of explosives in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

But for Metzger, the beginning of the end came in 1988.

In November of that year, he appeared with his son, John, on Geraldo Rivera’s daytime talk show for the “Young Hate Mongers” episode. In front of a national audience, the Metzger clan baited black civil-rights activist Roy Innis with racial slurs until Innis walked over and choked John with his bare hands. In the ensuing brawl, a white supremacist bodyguard broke Geraldo’s nose with a poorly aimed studio chair, thrown clear across the room. It was the show’s highest rated episode.

That same month, and with the disputed knowledge of Metzger, a crew of Portland skinheads would bludgeon Ethiopian immigrant Mulugeta Seraw to death with a baseball bat. Following the criminal trial, ambitious civil rights attorney Morris Dees of the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a civil suit against Metzger charging that the racist urged the skinheads to kill. The subject of The Nation reporter Elinor Langer’s book, A Hundred Little Hitlers, Dees’ controversial case singled out Metzger largely for his notoriety. Relying on hearsay and a plea-bargaining key witness, Dees argued that Metzger secretly ordered the murder, using his son, who had visited Portland to distribute hate literature earlier that year, as a messenger.

It was a convenient theory, allowing the public to blame a much despised, outside agitator for what, by many accounts, had long since become a local problem. In a move much criticized by journalists covering the trial, Metzger chose to represent himself, though he says with no money he had no other options. “I would rather have chewed broken glass,” he says. In any case, he lost, and his side was slapped with a $12.5 million judgment—$5 million from White Aryan Resistance, $3 million from Metzger, $4 million from his son and $500,000 from two of the murderers.

••• ••• •••

Besides the shaved head, Metzger has only his two chunky silver rings to identify him as anything but an old ranch hand. On his right hand is a horned devil, circled around the digit in swastikas. On the left, the head of a wolf bears two rows of jagged fangs.

To Metzger the ring is important, not just a wolf but a “Lone Wolf,” a symbol of that anti-government agent who, in the Timothy McVeigh model, assumes all the trappings of a normal life to conceal a radical political agenda. The most valued soldiers of the white-supremacist movement, Metzger says, no longer shave their heads or tattoo their bodies in crosses and swastikas. In the private sector, they hold steady jobs, and they strive for public positions of power—government, police, military.

“Lone Wolves are everywhere!” proclaims Metzger’s website, Resist.com. Of course, there’s no way to judge the actual number or power of so-called lone wolves in general or those loyal to Metzger specifically. “I’m more powerful than some people think and less than some others would believe,” Metzger says, rubbing palms over his eyes and speaking with grudging, almost pained honesty. “My weapon is propaganda now.”

With a post-9/11 public focused squarely on Islamic extremism, that weapon has lost significant force. Metzger still disseminates his views on his website, a twice weekly Internet radio broadcast and through a monthly newsletter, self-proclaimed “The Most Racist Newspaper on Earth,” and he grabs speaking events where his manager can find them. Earlier this year, they drove to Texas for one. In the early ’90s, he could draw crowds on three different continents.

In Japan, he met with intelligence officials and the chief of Tokyo’s police force, received samurai swords from the National Socialist Party and lectured a crowd of 400 elite businessmen and public officials. He has also met hostility. In 1992, he spent five days in a Toronto jail for reentering the country after a June rally for the right-wing Canadian Heritage Front. He later faked an appearance at the Century Plaza Hotel in Vancouver, calling authorities from a phone line routed through Victoria.

“I was giving them weather reports I got off the Internet,” he says, chuckling. “I told them, ‘I’m in a safe house and I can’t talk to you. I’m looking at the mountains and it’s a beautiful day.’ I had them convinced I was there.”

Anti-KKK protesters stormed the hotel and had to be forcibly removed by police riot squads. Metzger, having never left Fallbrook, watched the scene on TV. Germany, for obvious reasons, placed him on a watch list early, and England followed suit in 1993, banning him in advance of a nationwide speaking tour.

Now, no one pays for flight tickets to Europe or Japan, and on Tuesday nights, he relies on his manager, John Malpezzi, to drive him to karaoke night at the Packing House restaurant and bar.

Malpezzi is dawdling. A middle-aged man of full gray hair, he wears leather sandals, khaki shorts and a baggy gray T-shirt not baggy enough to hide a protruding beer belly. For much of the evening, he has been yelling boisterously at anyone standing within earshot and now is attempting to convince the same young blonde who had shadowed Metzger to instead “marry me for one night.” At his client’s beckoning, he trots over as fast as his wooden cane will carry him, waving both hands in a reverse, fish-was-this-big gesture.

“I was this close to that blond chick. Want to see the one I had over the weekend?” he asks, already pulling out a 4-by-6 of himself in a Tijuana bar standing next to an attractive, 21-year-old Mexican girl. “Gorgeous, huh?”

Nudging him to the parking lot, Metzger answers half-joking, half-insulting. “He’s a race mixer.”

Metzger is a racial separatist, not a white supremacist, he says. “I believe in complete racial separation as the best thing for all the races. Look at the civil-rights movement—do you think black people are really better off?”

Of course, he has made a career by advancing less judicial positions.

Alongside editorials on the threat of “Zionist Jews,” his newsletter and website feature cartoons of blacks with large, drooping lips; fly-covered Hispanics waiting in welfare lines; and sweating Jews with prominent noses, counting stacks of dollar bills. “The cartoons piss people off more than anything,” Metzger says, slapping his thigh.

His advocacy is also not strictly racial. Ascribing to the so-called “Third Position,” neither strictly left nor right politically, he criticizes “the institutionalized greed of capitalism” but laments the tyranny of the federal government over white workers. He scorns environmentally destructive corporations but unequivocally supports Europe’s turn-of-the-century colonization of Africa, the Caribbean and Asia. This year he endorsed the Rev. Al Sharpton for president, because “Tom Metzger knows a racist when he hears one.”

••• ••• •••

Malpezzi’s 1980, 240 D Mercedes is custard yellow. As he throws his cane in the backseat, Metzger spots a once-missing straw cowboy hat.

“You got my hat,” Metzger says, disappointed. “It’s flatter than a pancake.”

“Well, you let me borrow it.”

When Malpezzi flips the ignition, the engine bucks and wheezes, and when he sticks the automatic shifter into reverse, the clutch engages with a crash, shaking the car violently forward and back. Three men headed into the bar stop to stare, and he holds their unwanted attention by taking no less than five turns to line the car up before pulling out of the parking lot, full speed in reverse onto South Mission Road.

“Hey, watch it.”

“I got it. I got it. This car’s been on a lot of road trips,” Malpezzi shouts as the four-speed shudders into second and then third gear. “All over the country. Down in Tijuana this weekend, I had to bail my friend out of jail. What a nightmare. He went with a hooker and tried to screw her out of her money. Bad move. Always pay.”

“We got to get a new transmission.”

As the two bicker like an elderly couple, the car winds past Metzger’s old house, the one seized in his bankruptcy settlement with Dees, sold and now freshly renovated. Ironically, when he first came to Fallbrook in 1980, he moved into an all-Hispanic neighborhood. For security from outsider intruders—not his neighbors, he says—he surrounded his home with a 14-foot-high wire fence and mounted security cameras all over the roof. If he spotted trouble on one of the monitors, he would walk from the compound brandishing a sawed-off, double-barreled shotgun to cut off escape from the dead-end street.

“Nothing ever got stolen on my street,” he says, proudly. “No one even tagged it. The Mexicans, they like that.”

In the Packing House parking lot, Metzger points out the full moon—“Must be something wrong with you if you can’t get laid tonight”—as Malpezzi fishes for his cane.

Past the rows of dark brown leather booths, where middle-age couples sink in over steak and side salads soaked in too much ranch, Metzger veers left for the bar. In front of a red Marine Corps flag, the sign from the town’s now-defunct train station and two rows of black-and-white prints autographed by old country stars, a heavyset dyed blond in a black and tan blouse belts out the Billie Holiday version of “Stormy Weather.”

No one walks over to say hello, but several nod and smile or exchange greetings from their seats as Malpezzi grabs a table in the corner and Metzger strides immediately over to the stage to sign up for his turn to sing.

“He’ll marry you for one night,” Malpezzi hollers at a 17-year-old brunette sitting up front with her boyfriend.

“Hey, watch it,” Metzger cautions, protective more of his fidelity than the girl.

“They don’t get prettier than her,” the manager says lower. “She’s the kind of country girl you just want to do in the back of your pickup.”

For his first song, Metzger selects Albert King’s “Born Under a Bad Sign,” and croons along in a strange, halting Midwestern drawl, part blues and part lounge. He holds the microphone in his right hand, the cord trailing down his thigh, and squints intently at the lyrics on the video monitor. The words—“If it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all”—perfectly contrast his disposition.

Metzger cheers after every song and compliments the disc jockey, a tall man with slicked-back hair and Dick Clark cool, during a musical interlude. With a compact flashlight, he searches his booklet of karaoke CDs for other people’s favorites. When a man at the bar rushes over to harass him, Metzger smiles politely.

“I don’t agree with you,” the man shouts as if about to start throwing punches, eyes darting wildly. “Hey, asshole, listen to me. I dated a girl once who turned out to be a Nazi. You know what I did?”

“No.”

“I dumped her.”

Metzger shrugs, deferential. “Maybe she was the wrong Nazi.”

Metzger’s girlfriend, Mary, pulls up a chair as he winds down with his second pick, “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” a tribute to the bar’s former owner, Whitey, who carried a sawed-off shotgun strapped to his back and walked home every night with more than a $1,000 cash in his pocket. Mary wears gold loop earrings and red lipstick, a tan sweater-vest and matching suede boots. She has a settling air. “They call me mother. I don’t know why.”

Mary met Tom at Fallbrook Hospital, where she was passing through, selling medical supplies and Metzger was visiting a dying friend. “He was sitting in the waiting room there, and I couldn’t help but notice him,” Mary says, swooning. “He was just so handsome.”

She soon left Lubbock, Texas, and moved into the house they now share. They fight over the one working garage-door opener, go antiquing—“We’re garage-sale freaks”—and make annual pilgrimages to the Temecula Renaissance Fair, to which Metzger wears a Viking costume. They have two dogs, Bandit, Metzger’s half-coyote half-retriever, and Mary’s dachshund Pepper, the “Nasty Nazi.”

Through their front door, the kitchen on the left has a television screen with a live display of the driveway from a security camera, the only one left from his old setup. To the right is a short hall, where Metzger hung all his photographs—portraits of him with his former wife, his children and grandchildren opposite a painting of Robert Matthews, the anti-Semitic, anti-tax crusader. Matthews died in a shootout with federal agents in 1985, after his group, The Order, was implicated in a string of armed robberies and the murder of a Jewish talk-show host in Denver. In the painting, Matthews stands next to a portrait of a Viking ship, his right hand resting on a pistol resting on a Bible.

As a young redhead replaces Metzger on stage, Mary points up to her. “See the girl in black? She’s beautiful, totally Aryan. They’re dying out. In a generation, there won’t be any left. Tom likes real people, working people. He doesn’t like the idle rich, the idea of the rich who don’t know that the white race is dying, that don’t care.”

By the time the disc jockey asks around for last requests, Metzger has worked up a good buzz and is threatening a trip to the border the following morning. Adamant, he won’t let his girlfriend, Mary, or his manager, John, talk him out of it or pry an explanation from him. “No. I’ll meet you at the border tomorrow morning. We’re going to give ’em hell.”

With one song left, he chooses George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone.” “That’s my theme song.” He takes the stage smiling but quickly focuses on the monitor, ready to rehash the tired lyrics to the tired crowd.

“If I died tomorrow, I’d be pretty well satisfied,” Metzger says, looking satisfied. “I knew I wasn’t going to be the super leader to lead the white race out of oppression. The idea of revolution is that you toss gas all over the ground and somebody comes along, chucks a cigarette and—boom—revolution. I tossed a lot of gas.”